"But if I don't eat meat, where will I get my protein?"

The #1 question always asked when you tell them you live or recommend a:

100% Whole Food Plant Only Lifestyle.

Slaying The Protein Myth Eating Lower on the Food Chain:

A Plea for Sanity

By Ultra Endurance Athlete Rich Role

I am plant-based. Essentially, this means I don’t eat anything with a face or a mother. Animals find this agreeable.

I’m also an ultra-endurance athlete. Essentially, this means I don’t go all that fast, but I can go all day. My wife finds this agreeable.

Conventional wisdom is that “vegan” and “athlete” simply don’t get along—let’s call it irreconcilable differences.

I’m here to say that is utter BS.

“But where do you get your protein?”

Not a day goes by that I am not asked this question. If I had a dollar for every time this came up, everyone in my family would be driving a Tesla.

Most vegans bristle at the question. Armed for battle, they assume a defensive position and hunker down for the inevitable, age-old omnivore versus herbivore fight that always ensues. Because belief systems around food are entrenched—it’s right up there with religion and politics—emotions run high. Before you can blink, arrows are flying in both directions. Conversation becomes debate. And debate all too often devolves into mudslinging—an endless, hopelessly unproductive merry-go-round that leaves each side further entrenched in their preferred dogma and never leads anywhere constructive.

I hate that—it’s why a large portion of the general public find vegans so unpalatable.

Instead, I welcome the question. If someone is asking, I presume a genuine interest; simply an opportunity for a productive dialog.

So let’s try to have that dialog. The productive kind. My perspective on the elephant in the room—nothing more, nothing less.

We live in a society in which we have been willfully misled to believe that meat and dairy products are the sole source of dietary protein worthy of merit. Without copious amounts of animal protein, it’s impossible to be healthy, let alone perform as an athlete. The message is everywhere—from a recent (and wildly successful I might add) high-profile dairy lobby ad campaign pushing chocolate milk as the ultimate athletic recovery beverage (diabolically genius) to compelling food labels to a dizzying array of fitness expert testimonials. Protein, protein, protein—generally reinforced with the adage that more is better.

Whether you are a professional athlete or a couch potato, this hardened notion is so deeply ingrained into our collective belief system that to challenge its propriety is nothing short of anathema. But through direct experience I have come to believe that this pervasive notion is at best misleading, if not altogether utterly false, fueled by a well funded campaign of disinformation perpetuated by powerful and well-funded Big Food, Big Ag industrial animal agriculture interests that have spent countless marketing dollars to convince society that we absolutely need these products in order to breathe air in and out of our lungs.

The animal protein push is not only based on lies, it’s killing us, luring us to feast on a rotunda of factory farmed, hormone and pesticide induced low-fiber foods extremely high in saturated fat which—despite the current populist fervor over high fat, low carb diets—I remain convinced is indeed a contributing factor to our epidemic of heart disease (the world’s #1 killer) and many other western diet and lifestyle induced infirmities that have rendered our prosperous nation one of the sickest societies on Earth.

Indeed, protein is an essential nutrient, absolutely critical not just in building and repairing muscle tissue, but in the maintenance of a wide array of important bodily functions. But does it matter if our protein comes from plants rather than animals? And how much do we actually need?

Proteins consist of twenty different amino acids, eleven of which can be synthesized naturally by our bodies. The remaining nine—what we call essential amino acids—must be ingested from the foods we eat. So technically, our bodies require certain amino acids, not protein per se. But these nine essential amino acids are hardly the exclusive domain of the animal kingdom. In fact, they’re originally synthesized by plants and are found in meat and dairy products only because these animals have eaten plants. Admittedly, plant-based proteins are absorbed differently than animal proteins. And not all plant-based proteins are “complete”, containing all nine essential amino acids—two arguments all too often raised to negate the advisability of shunning animal products. But in truth, a well-rounded whole food plant-based diet that includes a colorful rotation of foods like sprouted grains, nuts, seeds, vegetables and legumes will satisfy the demanding protein needs of even the hardest training athlete—without the saturated fat that (despite recent studies to the contrary I take issue with) I am convinced contributes to heart disease, the casein that has been linked to the onset of a variety of diseases including cancer, or the whey—a highly processed, low grade discard of cheese production (another diabolical stroke of genius courtesy of the dairy industry that created a zillion dollar business out of stuff previously tossed in the garbage).

On a personal anecdotal level, adopting a plant-based lifestyle 8 years ago repaired my health wholesale and revitalized my middle-aged self to re-engage fitness in a new way. As hard as it may seem to believe, the truth is that my athletic accomplishments were achieved not in spite of my dietary shift but rather as direct result of adopting this new way of eating and living.

I’m not alone in this belief. Just ask Oakland Raiders defensive tackle David Carter. Watch this video of strongman Patrik Baboumian breaking a World Record for most weight carried by a human being when he hauled over 1200 pounds—roughly the weight of a Smart Car—10 meters across a stage in Toronto last year. Witness two-time World Champion Freerunner and parkour artist Timothy Shieff hopscotching off rooftops like a video game character and be amazed by this video of plant-based strength athlete freak-of-nature Frank Medrano doing things with his body you didn’t think possible. Then there’s MMA/UFC fighters like Mac Danzig, Jake Shields and James Wilks. Multisport athletes like Brendan Brazier, Rip Esselstyn and Ben Bostrom—a world renown motorcycle, mountain and road bike athlete & victorious member of this year’s Race Across America 4-man relay team; Professional triathlete & Ultraman World Champion Hillary Biscay who just raced her 66th Ironman; Ultramarathoners extraordinaire like Scott Jurek, his fruitarian compadre Michael Arnstein, and my old friend Jason Lester, with whom I completed 5 ironman distance triathlons on 5 Hawaiian islands in under a week who has since criss-crossed the USA on two feet and is currently prepping for a 100 day run across China. Then of course there is Timothy Bradley, Jr. who took down Manny Pacquiao last year (well kind of, but you get my drift).

The point is this: each of these athletes, and countless others, will all tell you the same thing: rather than steak, milk, eggs and whey supplements, opt instead to eat lower on the food chain and source your protein needs from healthy plant-based sources like black, kidney and pinto beans, almonds, lentils, hemp seeds, spirulina, quinoa, and dark leafy greens like spinach and broccoli.

Even if you ate nothing but fruit, you still would never suffer a protein deficiency—short of starving yourself, it’s almost impossible. Despite the incredibly heavy tax I impose on my body, training at times upwards of 25 hours per week for ultra-endurance events, this type of regimen has fueled me for years without any issues with respect to building lean muscle mass. In point of fact, I believe eating plant-based has significantly enhanced my ability to expedite physiological recovery between workouts—the holy grail of enhancing athletic performance. In fact, I can honestly say that at age 47, I am fitter than I have ever been, even when I was competing as a swimmer at a world-class level at Stanford in the late 1980’s.

And despite what you might have been told, I submit that more protein isn't better. Satisfy your requirement and leave it at that. With respect to athletes, to my knowledge no scientific study has ever shown that consumption of protein beyond the RDA advised 10 percent of daily calories stimulates additional muscle growth or expedites physiological repair induced by exercise stress. And yet most people—the overwhelming majority of whom are predominantly sedentary—generally consume upwards of 3-times the amount of daily protein required to thrive.

The protein craze isn’t just an unwarranted, over-hyped red herring, it’s harmful. Not only is there evidence that excess protein intake is often stored in fat cells, it contributes to the onset of a variety of diseases such as osteoporosis, cancer, impaired kidney function and heart disease.

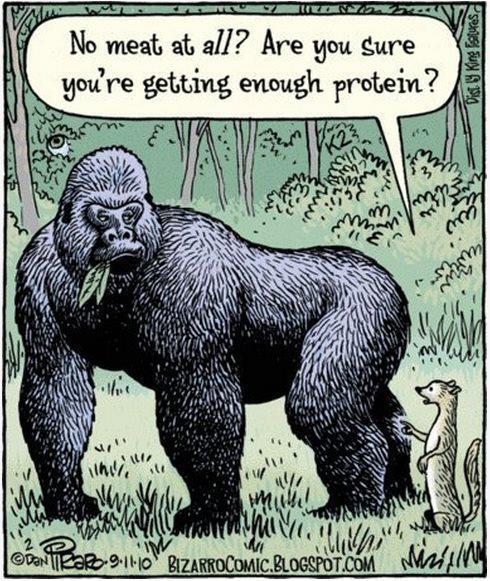

Still not convinced? Consider this: some of the fiercest animals in the world—the elephant, rhino, hippo and gorilla— are Plant powered herbivores. And nobody asks them where they get their protein.

Protein deficiency is a terrible thing. You may have seen the effects in pictures of the bloated bellies of starving children. Ironically, in industrialized countries, more health problems are the result of an excess of protein in the diet. It has become well established that too much fat can be harmful to one's health, but many people still mistakenly believe that there's no such thing as too much protein. That can be a serious mistake.

About 20% of our body is made up of proteins. Bones, skin, muscles, cartilage, all enzymes and some hormones are basically protein, in tens of thousands of complex chains of amino acids. Through a process known as protein turnover, our body breaks down proteins, recycling most amino acids. Some new amino acids must be added, and the proteins we eat are needed for nearly all our internal processes to continue. While plants and bacteria can manufacture all the necessary amino acids for their existence, humans can self-produce only thirteen. Those that are not required in the foods we eat, are called nonessential amino acids. Another nine amino acids that we need, the essential amino acids, must be supplied in the diet. All these can be obtained directly from plant foods (or indirectly from animals which have eaten plant foods). Contrary to what is often believed, it is not necessary to eat meat, fish or fowl to have all the essential amino acids in a balanced supply.

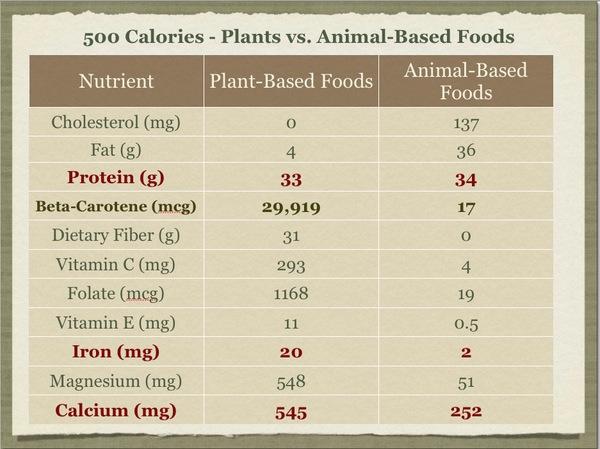

As the foods we eat are broken down into the various amino acids, the body's cells select what they need to make their building blocks. Since there are nine amino acids that cannot be made within the body, it is important to eat foods that supply these. Combinations of vegetables, grains and fruits supply these essential nine amino acids, even if eaten at different meals several hours apart. For optimum health and growth, adults need only 5% to 10% of their calories from protein. Meats, eggs and dairy products contain up to 40% protein but not all of it is available, due to difficulty in digesting them. Most vegetables and grains are reasonably low in protein, almost all of it available through digestion. Some beans (and a few vegetables) are as high in protein as meats, and when eaten with grains and vegetables, supply a healthful balance of complete protein, carbohydrates and fats.

The standard American diet is too high in animal proteins, leading to loss of calcium in the body. This can result in osteoporosis, a condition that makes bones brittle. Unfortunately, many people are told to drink milk and eat dairy foods to avoid or alleviate osteoporosis, but the high protein content in milk more than offsets the calcium it provides, so that milk may actually lead to calcium loss. High levels of protein also are known to be linked to kidney disease, resulting from the extra strain of filtering waste during protein breakdown. Animal protein and fats are linked to immune system deficiencies. To help your body prevent and fight disease, from flu to cancer, your immune system should be at its most efficient. Avoiding foods high in fat and cholesterol, as most animal foods are, and getting regular aerobic exercise is the best prescription for good health. Some weight training is also helpful in preventing bone loss.

An old myth that continues to circulate is that more protein is needed to gain greater strength and athletic performance. It has been repeatedly scientifically demonstrated this is not true. Excess protein is either excreted or, more commonly, converted to fat. Whether this extra protein is consumed in foods or in supplements, the body treats it in the same way.

Claims that one supplement has amino acids and is more readily absorbed than others is a reflection on how little the public knows about the body's use of proteins. For persons wanting to gain weight, these supplements are probably beneficial, but that gain will be primarily fat, not muscle, unless a rigorous exercise program is followed. Exercise is what builds muscles. Supplements and energy foods are never directly turned into muscle. Many other claims have been made for various amino acids, from curing diseases to preventing insomnia. There has been no scientific evidence that over-the-counter amino acid supplements cure anything, but large doses of some have been linked to the development of some health problems, and the FDA has tried to stop sales of mega-doses of amino acids.

The average American consumes over 100 grams of protein a day, more than three times the amount needed for optimum health and nutrition. For reversing heart disease you should limit your intake of protein to between ten and fifteen percent of calories. By eating a variety of vegetables, whole grains, legumes (beans, lentils, peas) and fruit you'll get all the protein you need.

From Rip Esseltyn of the Engine 2 Diet

Not only will you get all the protein you need, for the first time in your life you won’t suffer from an excess of it.

Ample amounts of protein are thriving in whole, natural plant-based foods. For example, spinach is 51 percent protein; mushrooms, 35 percent; beans, 26 percent; oatmeal, 16 percent; whole wheat pasta, 15 percent; corn, 12 percent; and potatoes, 11 percent.

What’s more, our body needs less protein than you may think. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the average 150-pound male requires only 22.5 grams of protein daily based on a 2,000 calorie a day diet, which means about 4.5 percent of calories should come from protein. (WHO recommends pregnant women get 6 percent of calories from protein.) Other nutritional organizations recommend as little as 2.5 percent of daily calories come from protein while the U.S. Food and Nutrition Board’s recommended daily allowance is 6 percent after a built-in safety margin; most Americans, however, are taking in 20 percent or more.

Doctors from my father to Dean Ornish to Joel Fuhrman, author of the best selling Eat to Live: The Revolutionary Formula for Fast and Sustained Weight Loss (Little, Brown), all suggest that getting an adequate amount of protein should be the least of your worries.

Look around you and tell me the last time you saw someone who was hospitalized for a protein deficiency. Or look around in nature, where you will notice that the largest and strongest animals, such as elephants, gorillas, hippos, and bison, are all plant eaters.

Also, the type of protein you consume is as important as the amount. If you are taking in most of your protein from animal-based foods, you’re getting not only too much protein, but also an acid-producing form that wreaks havoc on your system.

Why is protein so potentially harmful? Because your body can store carbohydrates and fats, but not protein. So if the protein content of your diet exceeds the amount you need, not only will your liver and kidneys become overburdened, but you will start leaching calcium from your bones to neutralize the excess animal protein that becomes acidic in the human body.

That’s why, in the case of protein, the adage “less is more” definitely applies. The average American consumes well over 100 grams daily—a dangerous amount. But if you eat a plant-strong diet, you’ll be getting neither too much nor too little protein, but an amount that’s just right.

Protein: Quality, Not Quantity Is Paramount

By Brendan Brazier Ironman Triathlete

Properly balanced plant-based protein can offer several advantages over more traditional animal-based options. I discovered this along the way when I was searching for a performance advantage. At the age of 15 I made the concerted decision that I wanted to race Ironman triathlons professionally. Aware that staking the odds of making this happen in my favor would rely heavily upon a sound nutritional strategy, I began to search for one. Going somewhat against the grain, I decided to experiment with a plant-based diet. As you might imagine, criticism flowed: where would I get my protein? Until it worked. I raced Ironman triathlons professionally for seven years, all on a plant-based diet. I honestly believe that the detail I applied to my nutrition program was a large reason for me even having a Pro Ironman career at all. The following is what I learned about protein and how you can apply it to boost your overall performance, improve muscle tone and increase your energy level.

It was once thought that only animal protein was complete and therefore a superior source to plant-based options. Complete protein is comprised of all ten essential amino acids. By definition, essential amino acids cannot be made by the body; they must be obtained through dietary sources. And, in fact, there are actually several complete plant protein sources. However, to obtain all amino acids in high quantities, it’s advantageous to consume several complementary sources of protein on a regular basis. For example, hemp, yellow pea and brown rice protein make up a superior amino acid profile that rivals any created in the animal kingdom.

Additionally, one of the big advantages of properly balance whole food, plant-based protein over animal protein is its only slightly acidic or neutral pH. In contrast, highly processed foods are acid forming, and even more so are animal based foods. Whey protein isolate, for example, is highly acid forming. Whey, strait from the cow, would be numeral and even slightly alkaline, but once the protein gets isolated (therefore rendering it no longer a whole food) and it is then pasteurized, these two steps of processing lower its pH, making it considerably more acid-forming. Meat, pork in particular, is also highly acid forming. Acid forming foods include all those that are cooked at a high temperature or highly processed. Among the most acid forming are meat, coffee, pasteurized milk and cheese, prescription drugs, margarine, artificial sweeteners, soft drinks and roast nuts as well as all refined flour-based foods. Refined flour-based foods include: most commercial breakfast cereal, white pasta, white bread, conventional baked goods.

As a basic rule, the more that has been done to the food, the more acid forming it will be. The less that has been done to alter its original state, the more alkaline forming it will be.

It’s advantageous to maintain a neutral pH. Eating too many acid forming foods will promote inflammation, reduce immune function and cause highly-alkaline calcium to be pulled from the bones to keep the blood in its neutral state of 7.35. This of course leads to lower bone density and in many cases, osteoporosis. In fact, the over consumption of highly refined foods is the reason that we as North Americans are contracting osteoporosis at a younger age than ever before in history.

The most alkaline forming foods are those with chlorophyll, the green pigment in many plants. Leafy greens for example. Hemp is an excellent example in that is contains complete protein, yet the fact that it is not isolated and that it contains chlorophyll helps maintain a more alkaline pH.

A large salad is also a good high-quality protein option. I realize that when many people think salad, protein is not usually what comes to mind. Although, dark types of lettuce are up to 40% protein and spinach registers at about 45% protein. Since leafy greens are light, of course, this doesn’t add up to astonishingly high numbers in term of grams of protein. However, since protein in leafy greens is already in amino acid form, the kind usable by the body, it doesn’t have to be converted; therefore it saves the consumer energy. The body can’t use protein as is, it must convert it to amino acids first. Therefore in my book Thrive: The Vegan Nutrition Guide to Optimal Performance in Sports and Life, I classify foods with this quality as “one-step nutrition” foods. They offer a significant advantage. Since the step of converting protein to amino acids is eliminated, the body will conserve energy through the assimilation process. And, because of this energy savings, you will have a greater amount. If you don’t spend it, you still have it; that’s the premise of another one of the core principals in Thrive called “energy through conservation as opposed to consumption.”

If a large enough salad is eaten, taking into consideration its “one-step nutrition” quality and therefore its ability to provide more energy than foods that don’t assimilate as efficiently, a substantial amount of usable protein will be ingested.

“Pseudo grain” is the term given to what is technically a seed, yet commonly referred to as a grain. Examples include: amaranth, buckwheat, quinoa and wild rice. Since they are all in fact seeds, their nutritional profile closely reflects that. They are gluten free, and higher in protein than grains. They can also be easily sprouted. The sprouting process converts the protein in pseudo grains into amino acids, putting them in the one-step nutrition category, thereby significantly improving their digestibility. Additionally, sprouting raises their pH making them an alkaline-forming food. And with greater than 20 percent protein in amino acid form and superior digestibility, pseudo grains are a sound protein source. Adding half a cup of sprouted buckwheat to a large salad will certainly yield a high-quality protein meal.

Animal Protein is the Problem

NOT the Cure!